Problem to solve: systemic inertia

Anyone who has spent enough time in a large organization must have witnessed the tragic power of systemic inertia. Even more so when it is a by-product of its company culture.

Cultural traditionalists —especially those born in or raised by the powers that be— expect, sustain, and even thrive on status quo for a living. The inertia that results from their long-standing but backward-looking methods and views are euphemistically repackaged as strategic sustainability. This way, they try to rationalize and justify the status quo. Tragically, they even see themselves as defenders of the long term.

Assisted by an army of conceptual architects, designers and other consultants, they spend person centuries and tons of money on all-encompassing yet paper visions of a corporate future that one day will solve all of today’s and tomorrow’s problems.

Their motto: Just wait and see, we’re almost there! Of course, they never are, and never will be. For the simple reason that the as-is world out there keeps moving at a higher speed than the desired to-be world can be designed — let alone realized.

In the meantime, among the lower ranks of the organization, people are exposed to the daily realities of business life: a fast changing competitive landscape, technological generations that last no more than a couple of years, and customers demanding reactive solutions, now. ICT professionals who take care of themselves and their career experiment with agile at scale, holacracy, DevOps, cloud computing and other aspects of the new normal. To fulfill their customers’ — and therefore their own — need for speed, they rightfully expect their organization to act as an adaptive, loosely coupled, self-organized and self-(re)organizing network of small, autonomous cells.

The bravest departments, teams and individuals don’t wait for corporate manna to fall out of the sky: they make the perilous desert journey from reality to vision by themselves. While they may have no final game plan, they are driven by strong intuition, belief and leadership — not necessarily personified by a current member of their formal management.

Solution: (partial) culture change

Corporate reality always has many moving parts, so fixing organizational sclerosis is never a walk in the park. The undertaking is not for the faint at heart. Especially since the corporate patient is not supposed to end up on the undertaker’s table.

For what it’s worth, here are a couple of truisms, i.e. commonly accepted truths or advice from the world out there. Take them at heart to prevent pernicious aspects of corporate culture from doing any further harm. Or not.

So, to whom it may concern:

#1. Adapt or die

Whether it’s your job, your life or your company: nothing lasts for ever. As evolution has shown, species can survive over thousands of generations. They do so by “selecting” slight variations in their individuals lucky enough to have adapted better than others to their changing environments. Seen holistically over time and from a distance, it looks as if the species has survived. Likewise, in order for a company (culture) to keep on thriving across generations, it needs to adapt every now and then. The driver for change, obviously, is the fast-moving political, socio-economical, business and technological environment. In organizations that rely on the status quo, aspects of corporate culture that once were a great asset “suddenly” become a liability.

In today’s turbulent times, hanging onto existing company culture can be reassuring: it gives a — possibly false! — sense of security and control. As said, the obvious danger is that the environment changes faster than you culture can afford. From the ancient civilizations to the Kodaks and Nokias of this world, the hard learning is this: adapt in time, or you will die.

Change brings (more) uncertainty, and uncertainty means risk. Nevertheless, the biggest risk is not to take enough risk, or not fast enough. Reinvent yourself, or someone else will.

#2. High-priests are just (wo)men in funny dresses

In any long-standing organization, culture is just as much a matter of emotional experience as of rational learning. That’s why it takes quite a while to fully integrate or assimilate into a new environment. Unfortunate consequence: strong cultures take more time to adapt, i.e. to unlearn, when such becomes a necessity.

Apart from norms, habits and regulations, company culture manifests itself in the cumulative language and vocabulary that corporate high-priests create, speak and disseminate among their followers. Cultural assimilation is complete when the words and their sometimes special meanings have been internalised to the extent that their usage feels natural and normal.

Eye-opener: however important high-priests may look, they are fundamentally just men or women in funny dresses. What I mean is: however valuable the high-priests’ statements have been historically, and however much their actions may seem logical to their followers today, their methods and techniques are not necessarily adapted to tomorrow’s problems.

To give cultural change a chance, it is vital to unmask the high-priests, and replace a sufficient number of them with people who can credibly represent the next cultural wave.

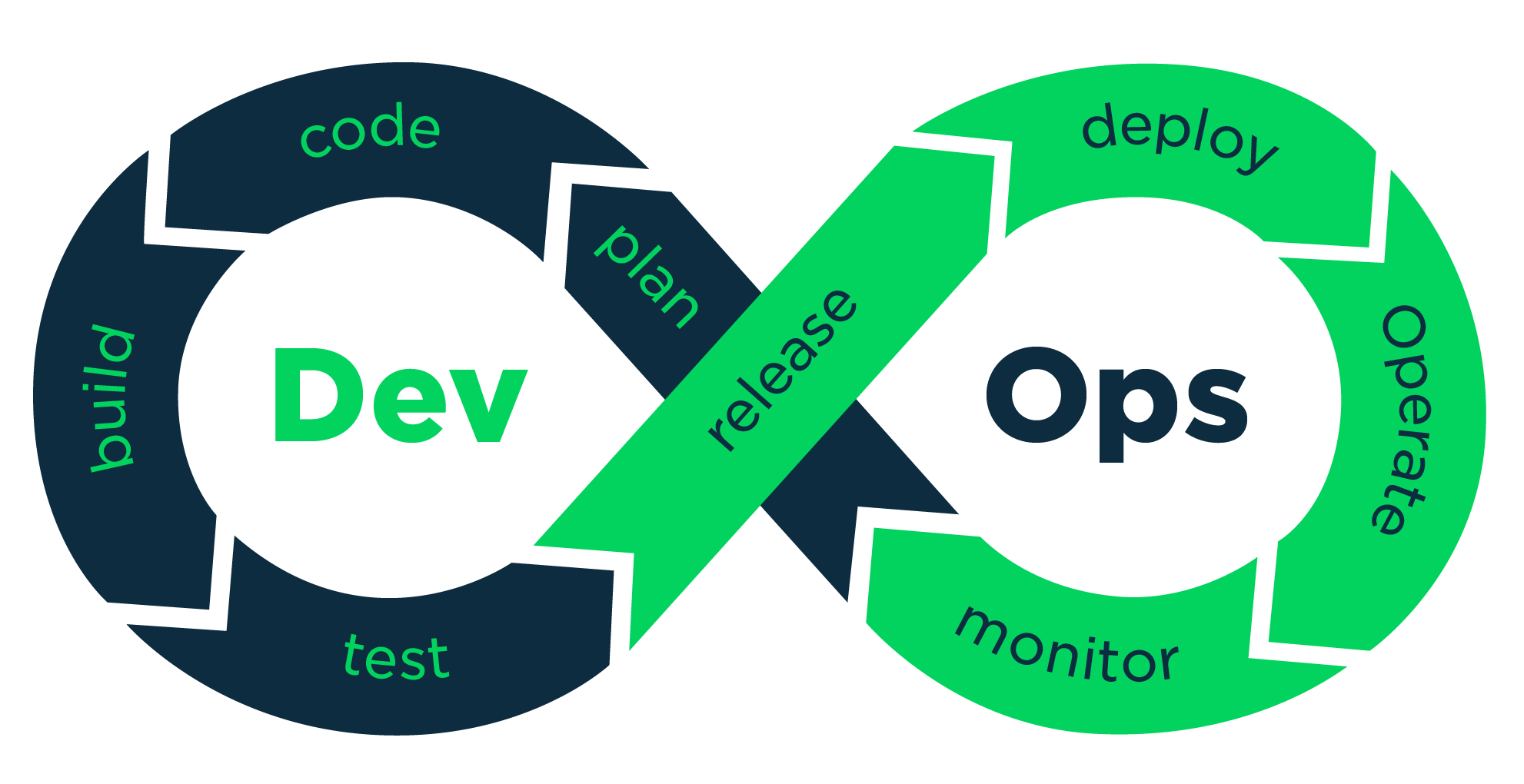

#3. Don’t just allow Agile and DevOps: embrace them

Any software professional who hasn’t been asleep for the last ten to fifteen years, knows that the Agile Movement, the DevOps approach and related initiatives have profoundly changed the nature of the ICT profession, across all industries. In these times of digital transformation, jumping onto these trains is an absolute no-brainer — which doesn’t mean it’s an easy task.

High-priests who proclaim that their followers are not ready (yet) for Agile, DevOps and the like, therefore totally miss the mark. They probably mean that they themselves are not able and/or willing to adapt — proving on the spot that they never will be.

Simple advice: Don’t listen to them, and do the right thing.

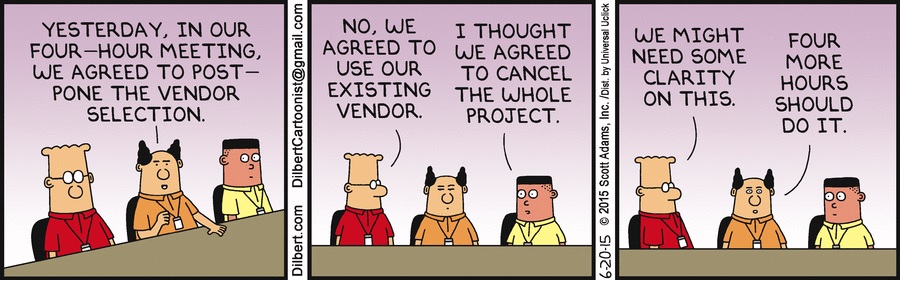

#4. Meet less, decide more

The number and quality of decisions is inversely proportional to the number of meeting platforms and participants involved in making them. In that spirit, I would strongly advise to:

- abolish any meeting platform that fails to gather at least half of its participants three times in a row

- never attend an agenda-less meeting: it is probably useless anyway

Some people justify the large number of meetings and meeting attendants by the need to create broad support throughout the organization. Which in turn is supposed to facilitate speedy execution after the decision is made.

In my experience, however, the “let’s get everyone on board up-front” approach boils down to to a self-inflicted veto power mechanism, as seen for example in the United Nations Security Council or the Council of the European Union. When world matters are at stake, thoughtful stability may make sense; when companies need to make and execute decisions fast, veto power kills progress.

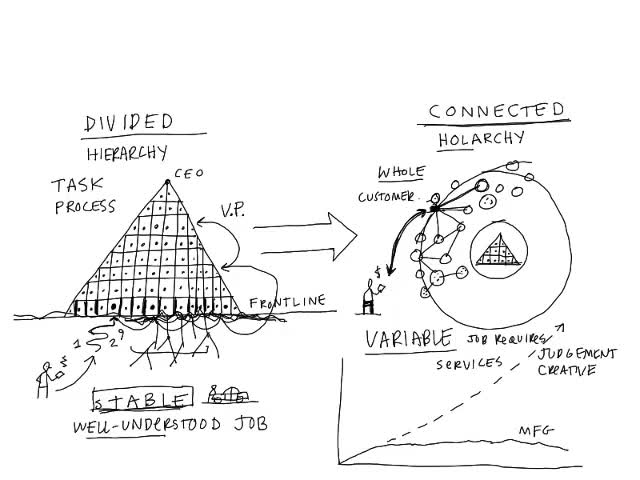

#5. Think networks, not hyperdimensional spaces

There is a good reason why MBA students all over the world are commonly exposed to Boston Consulting Group’s 2x2 matrices: that seems to be the maximum number of dimensions that ordinary mortals —including those same students, of course— are able to visually digest.

An “intelligent” yet static design of an organization that requires its members to think in three dimensions or more, stretches their mental capabilities: it makes it too hard for collaborators to understand their own place in the organization. Indeed, as more and more conceptual dimensions are added, the number of possible paths and connections through the organizational and terminological search space grows exponentially. Result: people can’t see the woods for the trees anymore.

Complex, adaptable organisms and organizations are able to prosper and function, though: examples from nature and biology abound. The condition is that the individual cells that make them up only need to know three things: their own purpose, that of their immediate dependents, and (possibly) which services their dependees use. How the cells want to operate internally, is for them —and only them— to decide.

Jeff Bezos’ famous 2002 API mandate is brilliant because it applies the principle of information abstraction to teams and information systems in one symbiotic go. To the outside world, the only thing that matters are the services offered, with a description of inputs and outputs, based on a common information exchange protocol (e.g. REST). From the inside, each team gets a mandate to pick whatever technology suits them best to implement their mission. There is no further need to get permissions from central boards or other kinds of people with veto power.

Amazon and any massively deployed microservice-based software application demonstrate, paradoxically so, the structural principles of our era: more complex yet less complicated organizations that organize themselves around simple principles, allow for more adaptability, flexibility and growth.

#6. Use generally available, state-of-the-art IT

The more complicated an organization is (re)designed and (re)built, the harder it is for its collaborators to find who is responsible for what. State of the art enterprise search technology becomes even more important then. The time when a company could develop a competitive advantage by building its own core information sharing systems lies at least two decades behind us: Google was founded in 1998.

Today’s knowledge workers are used to finding relevant information in fractions of a second. That’s not only true for millennials, by the way.

On the information storage and processing side, the cloud debate is over too. There is no need to build and push your own cart, when you can rent and drive someone else’s ten-ton truck. If you really must have your own, then buy one. That is, if you have the time.

But first and foremost, hire and train your proverbial truck drivers! They are the new bottleneck.

#7. Want to innovate? Build the path to production

To play the innovation game, many companies feel the need to externalize their efforts in so-called skunkworks or garages. There is certainly value in the argument that internal processes focusing on operational excellence would easily and immediately kill off any innovative approach. Backed by rules and regulations, corporate process watchers are very skilled indeed at fighting off non-compliant behaviour.

So from a short-term point of view, this makes some sense. In the longer run, however, there is more value in a fundamental revision of the rules and regulations that govern the core company information processes themselves.

Simply stated, companies need to make the following structural changes:

- less centralized control, more trust in distributed knowledge and skills (see fewer meetings)

- fewer committees, more self-organization and devolution of decision power (see Agile)

- fewer hand-overs from silo to silo, more customer-focused end-to-end thinking and automation (see DevOps)

- organize the company in terms of customer-focused value paths, that stream through networks of autonomous cells. Somewhat like physical goods that pass swiftly through a supply chain (see complex systems)

- less top-down and idealistic descriptions of hyperdimensional organizations with roles and functions, more focus on locally decided purpose, self-development and self-determination (see my other post on what to learn when and why)

- think less in terms of projects and portfolios. Bring work to (networks of) (teams of) people, rather than people to work

In short: rent, buy and/or build the innovation highway to production first: your ten-ton truck drivers will step forward, and use it.

Wanna bet?